Skills

Distraction & Motivation

Distraction can be an incredibly useful tool throughout recovery for both you and your loved one. It can be utilised at times of distress and to prevent or dampen down negative thoughts after meals.

The following is a list of distractions that can help. However, it’s best to find out what works for your loved one (and yourself).

This is not an exhaustive list:

- Card or board games

- Films & box sets

- Making things: scrap booking, making jewellery, poms poms, knitting, origami

- Painting nails

- Drawing, painting and doodling

- Word searches & puzzles, such as Sudoku

- Thinking about what they want in the future (non eating disorder related, low pressure – e.g. holiday, day trips etc.)

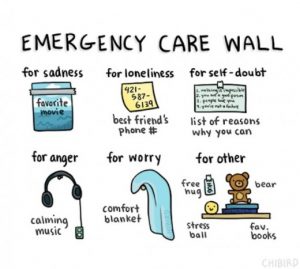

Completing the “emergency care wall” with your loved one may helpful for you both to know what to do in certain situations and what will help.

Motivation is slightly trickier, particularly in the early stages of treatment. Ambivalence plays a huge role in eating disorders and often young people feel the eating disorder provides safety and security. It may be hard for them to feel motivated to fight the eating disorder or the task of doing so may just feel too large. Some young people may feel that they don’t have a problem and actually for them the “positives” of having an eating disorder can outweigh the downsides, therefore reducing their motivation to change. This can change in time though and you can play a role in facilitating this change. One way of doing this is to use techniques that come from motivational interviewing.

Principles of Motivational Interviewing

- Expressing empathy – using active/reflective listening- neutral and unemotive. For example, “I can see this is really difficult for you”

- Develop discrepancy – create discrepancy in the young person’s mind between their past/present behaviour and future goals. Evoking change talk from your loved one rather than getting into an argument. For example, “What would you like to be different about your current situation?”, “What will happen if you don’t change?”, “What would you like your life to be like 3 years from now?”.

- Examine consequences – encourage your loved one to reflect on the pros and cons of staying the same or eliciting change.

- Avoid argumentation – avoid any approaches that may elicit resistance or defensiveness

- Roll with resistance – let their resistance be expressed, don’t suppress it.

- Support self-efficacy – support their confidence in their ability to change.

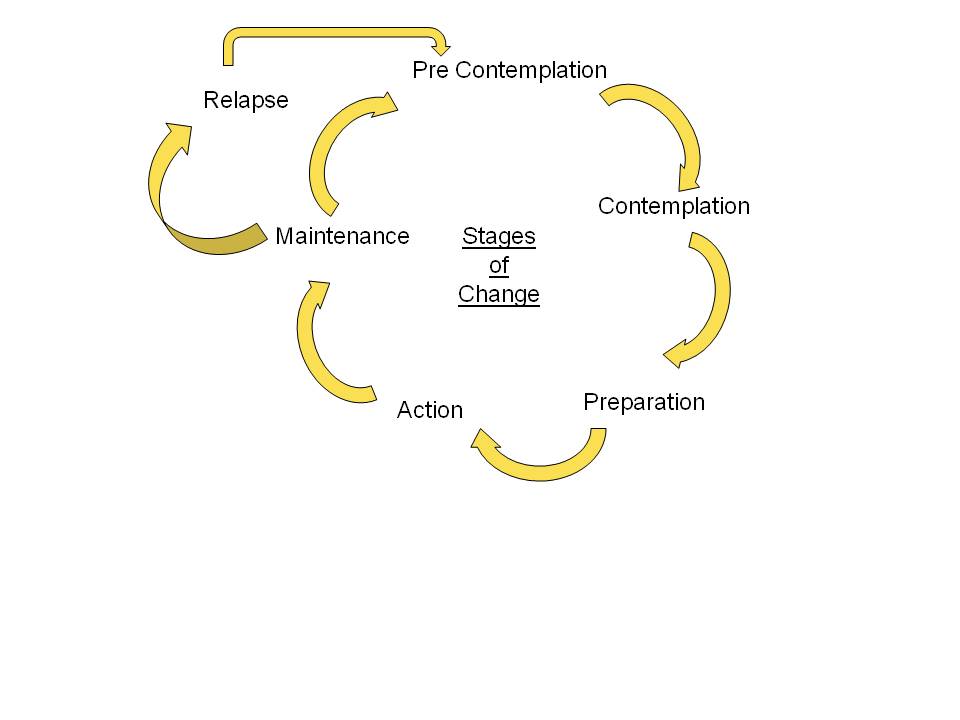

Below is the “Cycle of Change” model. This is just to give you an awareness of the Cyle of Change. A young person does not have to be in “action” stage to start treatment and often, young people aren’t. This doesn’t mean change can’t happen but may reflect why you will have to be the driving factor behind recovery for the your loved one for a while.

The Cycle Of Change is important when staging motivational communication.

This is a fluid model during the process of recovery for young people with eating disorders; a person can move through different stages, even in just a day.

Pre-Contemplation

Often, due to starvation or as part of the illness itself, your loved one cannot see the behaviours as a problem. It’s important not to get into an argument with your loved one about how unwell they are or try to use logic to get them to “understand”. They are not in the stage of change to allow this and you will end up frustrated.

It’s important you don’t fall into the trap of pretending everything is okay too; you know the eating disorder is there. Be aware of the symptoms and take these to your loved one, sharing your concerns. Try not scare them into admitting it though as it’s unlikely to work or be helpful.

Contemplation

This is more around the time when a person will know something has not being right and may be more accepting of support and help. However, they are likely to be very scared of change and what this may mean.

This is the time when it will be good for you to recognise eating disorder behaviours and symptoms. You don’t have to be the one to fix this on your own but it is helpful to be a listening ear for your loved one. If your loved one is over 18 and not in treatment, this may be a time to give them information about where to go for help and support.

Preparation

The person is ready to change. The person is aware of the impact the eating disorder is having on them and their family. Your loved one may be exploring ways to cope with eating disorder thoughts and feelings. They may able to share what they feel are barriers to recovery with you or clinicians in their team. This may be a time for them to identify specific eating disorder behaviours that have remained unchanged. It may a time to explore your role in their recovery with them as they may be more accepting of working with you. It may be helpful to think about your own and your family’s own ways of eating/attitudes, etc.

Action

This is when a person is ready to experiment with new ideas and will face fears in order to support change. This is the stage when a person will really work on things on their own (e.g. eating specific foods they identified themselves as scary). This is when your loved one may trust you and the treatment team. Your loved one may be most likely to ask for help and support in this stage from you and the treatment team. It important that you maintain boundaries around food and eating during this time yet be supportive and warm away from foods. It can be helpful to reinforce positive change but away from emphasis on weight, shape or food; so perhaps reflecting with your loved one on how much they may have in their life now (school, college, work, more independence).

Maintenance

Usually this stage is when the”action” stage has been happening from 6 months or longer. Your loved one will be able to resist any temptations to fall into eating disorder behaviours (e.g. when stressed, low or anxious). Eating disorder thoughts will take up less space in your loved one’s head but are likely to still be there somewhere. They may be developing new interests or returning to old ones before the eating disorder took over. It may be a point where you acknowledge how hard your loved one has worked to get here. It’s important to be aware of possible early warning signs of relapse and discussing these with your loved one and treatment team where possible.

Relapse

It is not uncommon given the nature of eating disorders and the rapid cycling between the different stages that there may be a “blip” or relapse.

It’s important in this stage to note where coping skills to maintain changes could have been better or areas your loved one has found difficult.

Away from food, it may be helpful to draw up a list with your loved one and find out what is good and bad about the eating disorder for them. This can be difficult and frustrating, especially as sometimes the good can outweigh the bad for them. But if you come back to it as time goes on, perhaps there will be a change and it also gives you an insight into how your loved one is feeling.